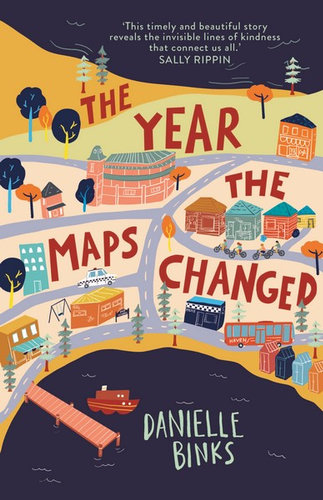

Danielle Binks, The Year the Maps Changed, Lothian Children’s Books, April 2020, 320pp., RRP $17.99 (pbk), ISBN 9780734419712.

Fred’s mother died when she was six and she’s always seen her step-father Luca as her dad, but now she has to share him and her house with his girlfriend Anika, and Anika’s son Sam. Things are changing fast, and Fred isn’t sure how to handle it all.

In Sorrento, Victoria, where Fred lives things are changing too. It’s 1999, and a group of Kosovar-Albanian refugees have been brought to a government ‘safe haven’ just outside of Sorrento. Through Fred’s eyes, we see the political manoeuvring on the news, the lines that get drawn in the community, and the refugees themselves and the issues that they face.

I admit that in 2020, when the world feels so heavy, I found it hard to read a book that deals with some of the things that Fred experiences even as sensitively as The Year the Maps Changed, and I would advise caution with some young readers. The book deals with the harsh politics of the refugee centre that was established at Sorrento, and the lives of the refugees there. It doesn’t shy away from details like the young girls in the centre asking to have their hair cut short to look more like boys for their own safety, even if Fred doesn’t understand the implications. There are also some fairly stark descriptions of the situation that the refugees have left behind via the news stories that Fred sees, and the disintegrating situation that they face in Australia.

The book also deals with Anika’s miscarriage, and it doesn’t shy away from that either. Throughout the whole book, I found the gap between what twelve year old Fred sees and hears and the adult-level implications underneath to be both intriguing and at times a little unsettling, and it may be worth parents or teachers reading it for themselves before handing it to a very sensitive young reader.

For the right reader, though, The Year the Maps Changed is going to be a very thought-provoking and touching read. Mature readers from eleven to fourteen will find a lot in Fred’s story, and it would make an interesting classroom text for grade six or seven classes delving into the complex and controversial history of Australia’s treatment of refugees.

Some strong themes that run throughout the book include family, connection and place, and Fred struggles with feeling disconnected from all of those. Her Pop has to go into hospital, and Luca’s girlfriend Anika and her son Sam have just moved into the house, so Fred’s time and connection with Luca are threatened. Anika is pregnant, and Fred will have to make space in her mother’s bedroom for the new baby, even while she questions how connected she really is to this infant, and Sam prods at her sense of connection further with reminders that Luca isn’t really her father.

Fault lines show up in her friendships, leaving her further disconnected when she finds out that one of her friends hasn’t been inviting her around because his father doesn’t approve of her family or their involvement with the refugees at the centre.

In parallel, cracks appear in the community around Fred when the refugees arrive. Most of the town want to welcome the refugees, but there are some who feel differently, and Fred isn’t sure how to deal with the fallout of those divisions, or how to help when the world that we see through her twelve year old eyes is far more complicated than she had realised.

Maps and names are recurring symbols used to great effect to illustrate the way that history and ownership is reshaped by political expediency. Fred’s teacher encourages his students to think deeper about how the lines on maps are drawn and redrawn, and place is a significant theme throughout the story. From the refugees’ broken sense of home to Fred’s distress as her lost sense of place within her house and her family, there is a recurring idea of dislocation.

The story also uses names to reinforce this idea. Fred reflects early on in the book about Indigenous place names and history, and the way that those names were changed, and the history obscured or erased by white settlers. Fred herself is a girl of many names. Everyone in her life has their own name for her – Fred, Winnie, Winnifred, Freddo – and each of those names is another aspect of her and reflects a different relationship and connection in her life.

We see the tricky subjectivity of maps and names and words crop up over and over again throughout the book, from the way that the situation at the ‘safe haven’ is reported in the news, to the way that the some of the locals see the refugees and talk about them, and the connections and divisions formed by and in spite of the language barriers.

What kept me reading, though, was Fred’s story. This twelve-year-old girl is very relatable as she struggles through the changes in the world around her, makes mistakes and tries harder. In the middle of life-changing crises and moments that feel too overwhelming, Fred’s story is about continuing to question the narratives around you, finding kindness and connection, and the kind of person you want to be. And that has never been more timely.

Reviewed by Emily Clarke