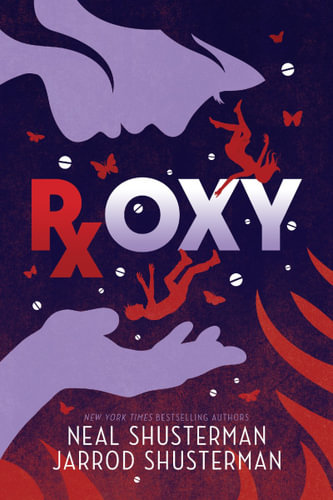

Neal Shusterman and Jarrod Shusterman, Roxy, Walker Books, November 2021, 400 pp., RRP $19.99 (pbk), ISBN 9781406392128

A horrifying perspective on the crisis referred to as the opioid epidemic by the New York Times bestselling father and son team, Neal Schusterman and Jarrod Shusterman.

Quite honestly, I struggled to get a handle on this story at first, and then suddenly it all began to make sense. Once the penny dropped, I found this book to be a beautifully moving, timely, relevant and incredibly compelling story reaching into the dark and often fatal world of substance abuse. And readers if you look closely there is a little clue hidden in the cover art which you might find provides you with an insight into the story.

The father and son co-authors Schusterman have explored the increasingly dangerous drug environment, in particular the crisis referred to as the opioid epidemic and focussed on the lives shattered by addiction in a most unique, original, and creative way.

Above our human world a party endlessly rages. It is always night-time, the bar is always open for business, the music ‘pumping’ and these lofty heights provide a spectacular view of the city below. Humans identify the partygoers simply as narcotics, opioids, drugs. But here they are malevolent gods, toying with the fates of mortals. Roxy (Oxycontin) and Addison (Adderall) have made a wager to see who can be the most lethal, the quickest.

So, in Roxy, the substances – all varieties of drugs and alcohol – are all personified. Furthermore, the personification of these substances, gives them power, presence, intent, and a pervading sense of evil. Dichotomous in ‘nature’ they are ruthless and yet seductive, addictive and yet euphoric, dangerous and yet comforting. Positioned in a upline/downline hierarchy, reminiscent of the gods of Roman and Greek mythology, there exists several degrees of power, with the most addictive and damaging drugs on the highest level, and all their less lethal, but adequately addictive, drug relations in their downline. Evidence that the opioid epidemic has three phases (prescription opioids, heroin and the cheaper-more potent synthetic opioids such as fentanyl), is referenced and also that plenty of people who start on one often die on another is a stark reminder of the downward spiral of substance abuse.

Isaac and Ivy Ramey are their targets. Ivy is under stimulated and overmedicated. Isaac is desperate to recover from a sports injury that jeopardises his chance of a football scholarship. This is the start of a race to the bottom that will determine life and death. One Ramey will land on their wobbly feet. The other will be lost to the excesses of the Party.

In the chapters that are told from the substances’ perspective, the reader quickly realises the stronghold that a drug has on its user. An insatiable hunger that cannot be staved off, so much so that often users aren’t taking opiates to get high as much as to avoid the agony of withdrawal. A perfect case of supply and demand.

This story is alternated with chapters where the human characters, a brother and sister who love and care for each other, but nonetheless are battling with the uncertainty that comes with being teenagers, convey their vulnerability. A Mum and Dad who want what is best for their children in a confused and convoluted sort of way and the family’s matriarch, a beloved grandmother loved by all. It is through these complex relationships that the reader senses a growing intensity of emotions, coupled with a foreboding anticipation of what lies ahead.

They have friends, lives, dreams, and goals and in the background, at least at the beginning, these drugs.

Readers are encouraged to consider the opioid crisis not as a result of a few weak people, addicts of bad character who simply get ‘hooked’, but to also consider that many addicts, from all walks of life, are fearful of arrest and the shame that goes with addiction. As a result, many people hide their drug use in ways that increase their risk of a fatal overdose, particularly when people use alone.

I am good at what I do. More than good. I am the best. … I am more than life and death. I am the fire that burns through the world. I am the luminary at the leading edge of a glorious pandemic, and all their attempts to contain me have failed. Why should I feel shame at that? Why should I feel remorse for that boy who lay dying in a dark room? He’s the one who came to me, after all. He abused me. So why should I weep another tear? He reaped what he sowed.

I found this book to be creative, compelling, and frightening. It carries a poignant message for both the individual and society as a whole.

Recommended for readers 15+ years.

Reviewed by Julie Deane