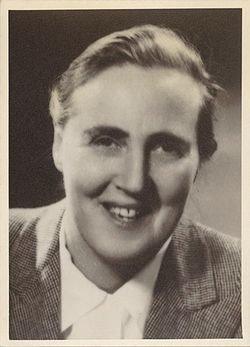

Nancen Beryl Masterman was born in 1900, in Middlesex in the south of England and grew up as an Edwardian child acquiring the language, idiom and accent of her parents’ social class. She had a twin Jan and four other siblings. Her mother, Lilla, (from a successful London Osmond family) and father, Charles, told them stories and read from the rich tradition that English literature provided. Her father had attended the great English public school, Charterhouse, to which he had sent his eldest son, Kay, and her mother had been to a school run by one of the early suffragists, Francis Buss, who was a leader in the development of girls’ education at the end of the nineteenth century.

Nan was part of a comfortable upper middle class family with servants and tutors until an event that featured in Victorian novels occurred – the family ran into financial difficulties because of the father’s loss in a court case – and the Mastermans immigrated to the wilds of Tasmania.

Life in a strange land

Nan’s life had many of the features of an adventure story in which remoteness and a variety of struggles play an important part. In 1914 Charles purchased a property at Bagdad, a tiny bush town and staging post on the road to Launceston. With this property – now Chauncy Vale –the family were involved in clearing the ground for orchard use – an optimistic plan that never succeeded. It was a hands‐on lesson for the family in Tasmanian landscape, landforms, flora and fauna.

The indefatigable Lilla ensured that her children went to private schools, with Kay, the eldest son taking up a scholarship at the University of Tasmania. However, St Michael’s Collegiate did not suit Nan as she was the target of xenophobic taunts including ‘Chinky’ and ‘Queen Hayseed Pommie’. So, Nan left school in 1916, becoming involved with the Bagdad homestead, bush walking with Kay in the rugged south west of the state and later attending Girl Guide College in England.

A prelude to a writer’s life

At end of the twenties, Nan joined her twin to live on a houseboat on the Thames, where she wrote her only unpublished novel, Comfort me with Apples. She travelled widely, teaching English in Denmark, Scandinavia and Russia. In 1938 she left for Australia from Holland on the Meliskerk. The menace of Fascism saw large numbers of people seeking refuge and Nan met a German Jewish refugee, Helmut Anton Rosenfeld, and they married in Victoria after Nan’s return. With the second war against Germany it was not a good time to have a German sounding name in Tasmania and they changed their name to Chauncy, a Masterman family name. From Bagdad and in her brother’s house ‘Day Dawn’, given as a wedding present, Nan made her income writing scripts for the ABC.

In 1947, Nan made a promising start to her literary career with one of her most successful novels for children, They Found a Cave, the first of her fourteen novels. Four English orphans – Cherry, Nigel, Brick and Nippy – migrate to Tasmania, to the care of their Aunt Jandie (aunts are recurring characters featured in Chauncy fictions as they do in Nan’s own life) on her farm outside Hobart. Their arrival is greeted with enthusiasm by young farm boy ‘Tas’, and weeks of exploration and good times follow before Aunt Jandie goes to hospital, leaving the children in the care of Ma and Pa Pinner, her foreman and housekeeper.

A few days of tyrannical treatment by the Pinners force the children to seek refuge in a secret cave, where they set up home to await the return of Jandie.

As with most of Chauncy’s novels there are moments of Nan’s personal experience woven into the story and a sense of the melodramatic in the plot.

An established author

Between 1958 and 1961 Nan’s novels won her the award of the Children’s Book of the Year three times – twice for the Lorenny family novels Tiger in the Bush and Devil’s Hill. In these and other novels, she expresses admiration for the pioneering life and high regard for the families that learnt their resilience and respect for the environment from a direct and gritty experience of nature; a crucial insight into Chauncy’s world view.

In 1961 the third winning novel Tangara, a time slip story, revealed Nan Chauncy’s concern about the treatment of the Tasmanian aborigines who, she believed, had been wiped out by the rapacious treatment of white settlers. Tangara is a deeply moving classic by one of our great children’s writers; it is part fantasy, part history and one hundred percent masterpiece.

Between 1964 and 1968 Chauncy’s Roaring 40, High and Haunted Island and Mathinna’s People were commended by the Children’s Book Council of Australia. Nan had established herself as an esteemed Australian children’s author. Mathinna’s People, published in 1967, is a very demanding book for a young readership. It tells the story of what might be called a stolen child, the little girl pictured in a red dress in the 1842 portrait by Thomas Bock. Mathinna is taken by the Governor of Tasmania to live with him. When the Governor and family are recalled to England, Mathinna is left in the care of a Dickensian style orphanage that proves very unsatisfactory. Mathinna ends her life early exchanging her body for drink.

Nan Chauncy was the first Australian author to be awarded the international honour of the Hans Christian Andersen Diploma of Merit in 1961 ‘for the body of her work’.

A legacy of quality

Winning three Children’s Book of the Year Awards in a period that heralded the establishment of ‘a literature for young Australians’ indicates Nan’s acceptance as an esteemed Australian children’s author. She takes her place alongside much praised and award-winning writers such as Hesba Brinsmead, Ivan Southall, Colin Thiele, Patricia Wrightson, Joan Phipson and Eleanor Spence. Her novels were translated into thirteen languages and braille.

Her death from cancer in 1970 was felt as a loss to more than the Chauncy family. For over twenty years she had featured Tasmania in her writing. Nan Chauncy wrote about young people who have to show personal strength as they cope with nature away from the comforts and supports of manicured urban life. Her writing coincided with a worldwide desire to save nature from the depredations of uncontrolled exploitation and industrialisation. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published in 1962, the forerunner of a widespread and international concern with pollution and climate. No small wonder that the family bequeathed their beloved property as a conservation area for Tasmanians to enjoy. Nan also wrote about the horrors that overtook Aboriginal life and her writing gave them recognition; she was well ahead of her times in that regard.

Nan had placed Tasmania firmly on the literary map. The Tasmanian Premier’s Department quotes with approval John Marsden’s comment: ‘No ranking in Australian children’s literature is too high for Nan Chauncy’.

Notes

Notes

This extract is taken from a talk Hugo McCann gave at the launch of the Travelling Suitcase Exhibition at the Hobart LINC. The exhibition of Nan Chauncy’s novels, images and memorabilia is touring through the Tasmanian library system throughout 2015, engaging families and individuals in an enthusiastic rediscovery of the author and recognition of her contribution to Tasmanian and Australian literary life and culture.

Hugo McCann is a retired Lecturer in Children’s Literature from the University of Tasmania who has been Awards Coordinator for the CBCA Book of the Year Awards and is a Life Member of CBCA (Tasmanian Branch).

They Found a Cave was made into a movie in 1962, winning Best Children’s Film at the Venice Film Festival. In 1988, the Australian Children’s Television Foundation adapted Devil’s Hill for TV to celebrate the Australian Bicentenary.

The ‘Year of Celebrating Nan Chauncy in Tasmania’ organised by CBCA (Tasmanian Branch) features the Travelling Suitcase Exhibition, the Nan Chauncy Oration delivered by John Marsden to a packed audience on 20 June, sell out screenings of They Found a Cave and a Picnic at Chauncy Vale on 11 October. For more information see the CBCA (Tasmanian Branch) website.