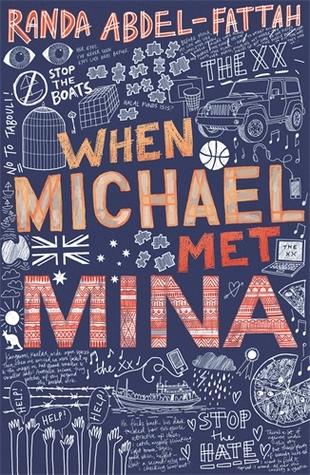

We asked author, Randa Abdel-Fattah to tell us a little about how her timely YA novel, When Michael Met Mina developed. Her answer is of course, gracious and thoughtful. The book explores topics not only of interest to Australian young people, but also to many others across the globe.

How does racism affect people’s everyday lives? How does it affect the victims– and the racists, too? Just over three and a half years’ ago I quit law and started a PhD to explore just that question. I wanted to unpack racism, specifically Islamophobia, from the point of view of its perpetrators. While I was conducting my fieldwork, interviewing people, attending anti-Islam and anti-refugee rallies (challenging ugh stuff), a character popped into my head. Well, two to be precise. One was a young Afghan refugee. A ‘boat person’ we see maligned and stigmatized by both sides of politics. Bright, fierce, courageous, scarred, she wouldn’t budge from my head. I thought about what it would mean for this young girl to have fled Afghanistan, grow up in Western Sydney, only for me to then throw her into a private school in the lower north shore of Sydney. I called her Mina.

The other person who popped into my head at one of the rallies I was attending was a boy called Michael. As I interviewed people about their ‘fears of being swamped by boats’, about the ‘Islamisation of Australia’, about the so-called ‘clash of civilisations’, I wondered what it would mean to be a teenager growing up in a family peddling such racism and paranoia. How do you ‘unlearn’ racism? How do you find the courage to question your parents’ beliefs? How do you accept responsibility for learning about the world on your own terms? That’s when I decided to write a story that took these two characters, Michael and Mina, and threw them at each other. As I was writing the book I was also writing my PhD thesis. On the one hand, I was exploring the ‘academic’ and theoretical. On the other, I was bringing characters to life who would allow me to experiment with the lived reality of these theories. It was an incredibly exciting, challenging and cathartic experience. I cared deeply about my characters because I felt so much was at stake. So much of their trauma, angst and battles were unfolding in the political and public space as I wrote. Sometimes I would write a scene and within days or weeks the scene would become reality: an incident of abuse, asylum seekers being caught working and returned to detention and so on. Whenever that happened, I felt raw, as though I couldn’t control the line between reality and fiction. But ultimately, with a young adult book, the thing that keeps you going is hope. Incredible, passionate, joyous hope. And that is what makes every moment of despair pale into insignificance. I have complete faith and trust that younger generations will rise up against racism and hate.