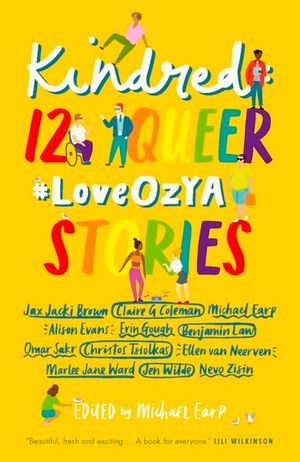

Michael Earp, (ed.), Kindred: 12 Queer #LoveOzYA Stories, Walker Books Australia, June 2019, 320 pp., RRP $24.99 (pbk), ISBN 9781760651039

The twelve short stories in this collection reflect the inclusive and intersectional Australian LBGTQIA+ community. Some are more successful than others. In several stories, the use of non-gender specific pronouns for non-binary characters takes a bit of getting used to, but like all new terminology, the more it’s used, the more comfortable it will be. According to wikipedia “Some non-binary/genderqueer people prefer to use gender-neutral pronouns. Usage of singular ‘they’, ‘their’ and ‘them’ is the most common; and ze, sie, hir, co, and ey are used as well. Some others prefer the conventional gender-specific

As some content is quite explicit, I would recommend this collection for readers 14 years +.

Rats by Marlee Jane Ward. Michelle is a Rat, living in the tunnels under Melbourne Central Station. Ward has created a frighteningly believable future, where kids live in fear of being rounded up by The Feds who will “shave your head and send you to a kid factory where you haft work day and night.” It may be the future, but it has a definite Dickensian flavour to it. Michelle literally collides with Maita, and she’s smitten. This is a very sweet story about falling in love in a harsh environment.

In Case of Emergency, Break Glass by Erin Gough. Amy works for Cassie’s Catering, and is dating Steven. Amy is ambivalent about her feelings for Steven; “It’s just that when they kiss, her mind drifts….” Maybe kissing is just not her thing? While catering for a party in an opulent mansion, she meets Reg, whose arms are “like something from a natural history bookplate”; inked with all sorts of birds. Reg mesmerises Amy with her poetic descriptions of how it would be to fly like a bird. There is something very ethereal and mysterious about Reg. This is a love story, and also a call to conserve the ecology of our dwindling forests.

Bitter Draught by Michael Earp. Earp’s story reads like a fairytale, complete with apothecaries and witches. Simeon and Wyll have grown up together in a small village community, where relationships appear not to be judged by gender. Reference is made to the blacksmith’s daughter, who has mothers (plural), and Simeon’s mother tells him that Wyll “is a keeper”. Earp uses non-binary singular pronouns for the character of the witch, Wren; “tall and earthy, their long, dark hair falls straight to their hips.” This is a shift in language that is confusing to start, but it doesn’t take long for the reader to get used to it. The witch sends the boys on a quest that will change the course of their lives. As Wren tells them “The truth is a draught of its own. Bitter to swallow, it heals in time.”

I Like your Rotation by Jax Jacki Brown. Jem sees Drew at the swimming pool and immediately thinks “I’m not alone.” Jem and Drew are both in wheelchairs. Drew is a little older and is confident about her queerness; Jem is still coming to terms with her sexuality. Brown’s story contains a lot of anger, which is reflected in her characters responses, particularly to any assistance offered by able-bodied people. “Why do people think I always need help?” Jem wonders. Brown has tackled disabled representation within pride with truth and honesty.

Sweet by Claire G. Coleman. Coleman has created a future world where gender is disguised and seen as something to be hidden. Roxy and her friends hang out at Underground, a sub-basement nightclub where no questions are asked about underage clients. As the only black kids at school, the gang were drawn together “back to back, fists outwards in the schoolyard.” This story brings together issues of racism, sexism and what it is to love in a world were sex and gender are taboo. Coleman uses role reversal and readers should be aware that there is content expressing transphobia.

Light Bulb by Nevo Zisin. I found this story particularly painful to read. Zisin uses the metaphor of physical pain to describe the psychological pain of being confused and marginalised as a non-binary person: “I wanted to be treated like me, to be asked what I was looking for as a person and not as a gender.” Searingly and brutally honest.

Waiting by Jen Wilde. This story made me cringe. It brought back too many memories of adolescence, and toxic friendships. While waiting in a queue for the PrideCon festival, Audrey meets a group of girls who make her feel included. For the first time in her life she has found her tribe. Will she find the strength to cut herself lose from her very toxic ‘friend’ Vanessa, who has controlled her for too many years? Three cheers for Audrey!

Laura Nyro at the Wedding by Christos Tsiolkas. This story doesn’t fit with the rest of this collection – it’s written for an adult audience. It’s about a gay couple, who’ve been together for ages, who decide to get married. They are grown men, and I felt the story was not suited to a YA audience. It made me feel a bit uncomfortable, and I’m not sure why Michael Earp felt it was appropriate to include it. Its reference to pedophilia should also carry a trigger warning.

Each City by Ellen van Neerven. This story is a glimpse into a near future, where an Indigenous musician who uses her hip-hop music to make political statements finds herself on the run from those in power. It’s easy to forget how lucky we are in Australia to be able to make our voices heard without any fear of punishment or reprisal. Each City reminds us that we need to appreciate this freedom, and be vigilant to any changes to that freedom.

An Arab Werewolf in Liverpool by Omar Sakr. This story about Wafat and Noah’s ‘secret’ love shines a light on family expectations, no matter what cultural background. Sakr’s descriptions of young love are raw and true. And funny – this story made me giggle with its youthful exuberance.

Stormlines by Alison Evans. Marling and New are thrown together in a mangrove after a huge storm. “The globe is hot, they say” and the world is suffering from the effects of global warming. In this topsy turvy world, Marling needs to decide where they’re going to call home, and who they will share this home with.

Questions to Ask Straight Relatives by Benjamin Law. Thank you Benjamin for finishing this collection with a self-deprecating piece on how it is to be the only queer in the family. By using humour to make his point, Law has hit the sweet spot with this story – funny and poignant. As he says “being queer means we’re positioned to see the world fundamentally differently.”

Reviewed by Gaby Meares