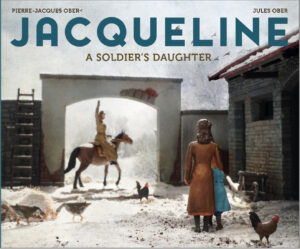

Jules and Pierre-Jacques Ober, creators of Jacqueline: A Soldier’s Daughter speak to Reading Time reviewer, Kevin Brophy about their book, published by Ford Street Publishing.

Firstly, congratulations on your new book of illustrated children’s history being listed as a CBCA Notable book. Can you give us some background to the inspiration behind your story, Jacqueline?

Pierre-Jacques: Thank you Kevin ! Yes, it is always very satisfying and reassuring to be acknowledged by an institution such as the CBCA.

Jacqueline was a natural choice to follow The Good Son and the story of Pierre. We are using photos of miniatures to visually illustrate the stories and our first book played on the metaphor of the ‘little soldier’ lost in the great war. For our second book I wanted to express what it might feel like to be ‘small in the big world’ of adults.

I also wanted the main character to be of the same age as our readers (between 7 and 12) . Our first book was so sad, so the second had to have a happy ending! Finally, I wanted to continue to explore one of our main themes: that war is never the answer.

So I remembered that, a few years back, my mother had written her memoirs for my sister and I. When I read the chapters relating to her experience during WW2, I discovered the story I was looking for. My mother was 7 years old when the Second World War started and 12 when it finished. During those 5 years she was totally carried along by a world of adults gone mad. And it took her 5 years of displacement and drama to finally see her most cherished dream fulfilled. I don’t want to give away the (happy) ending but it demonstrates very strongly the sheer absurdity of war and the concept of ‘the enemy’.

I would like to add that all my stories are about love – the best source of inspiration for me. Filial love and love for one’s country in The Good Son, marital and family love in Jacqueline.

You are a husband-and-wife team, and your first book together has won multiple prizes in Australia and in France, and now your second looks like being a prize-winner too. Your books are so stunningly beautiful, so sensitive to the ways images can tell stories, and unique in the manner and style of the illustrations. Can you tell us how you manage the division of ‘labour’ in making a book – and how you manage the space in your house to do this at home?

Jules: Thank you for your kind words. Nothing makes us happier than when someone tells us they were touched by our books.

The Good Son won the 2019 Prix Sorcières, the most prestigious children book award in France in the category “most beautiful book”. In Australia it has been shortlisted for the 2020 CBCA Picture Book of the Year and was the winner of the NSW Premier’s Young People’s History Prize. Jacqueline has just won le Prix HiP du livre de photographie francophone 2021.

Prizes are of course exciting and it’s wonderful to be acknowledged by our peers, but do you know what gave us the biggest thrill? To see our first book on display in our local library. That was a real buzz. We were so proud.

Strictly speaking, our process is in fact not strict – it’s pliable and organic: it is Pierre-Jacques who starts with an idea for a story. He then spends a huge amount of time researching all the possible figurines, sets and props that might be sourced in order to bring the story to life. He trawls online hobby shops around the world to find the appropriate costumes and poses for the story in mind. Once he is convinced that it will be possible to tell the story with miniatures, we start ordering them ( our technique is very expensive!). Then we wait – sometimes for months – for these little packages to arrive on our Melbourne doorstep.

During that time, Pierre-Jacques starts to storyboard the pages. Then comes painting and construction until finally, one day, we are ready to begin photography and that’s where I come in. It’s often at this stage that the story will start to take different turns. As the characters come to life in the viewfinder of the camera, they sometimes inform a diversion from the intended storyline. I’m sure this might happen for writers/directors who come across a particularly talented actor. This can be really frustrating for PJ, but we always manage to work together to roll with these changes for the betterment of the final book. PJ has a background in film, so his approach can be very cinematic. Whilst PJ has an intellectual and philosophical approach to storytelling, I am very visual and intuitive. Ultimately, the most fascinating aspect of our work is the fact that often it is the figurines themselves who help us refine the story, a scene or a sequence. By photographing these tiny figures (from 1:87 to 1:35 scale ), I actually get to ‘meet them’. To the naked eye, the details of their little faces are not really visible. Through the lens I discover who they are and can then reveal their emotions via things like body language – sometimes tilting a tiny head, or emphasizing the droop of little shoulders.

To answer the final part of your question, we are able to produce our books on a simple table set in front of the window of our office. Our Lilliputian world allows us to set up grand scenes on a small surface.

Jacqueline could be read as a story showing how children are affected by war. This theme is sadly topical now with so many women and children fleeing the war in Ukraine. Clearly your books are works of love and dedication, so what were your motivations for developing this story of children in war?

Pierre-Jacques and Jules : Our motivations are very similar to the inspiration behind Jacqueline’s story mentioned earlier. The overarching message of our books is that it is always the “little people”, the civilians who suffer the most as a result of war. Men are of course also suffering, but they are part of an army. They can find a minimum of comfort and strength in camaraderie and sense of purpose. The civilians suffer either directly by being killed, or emotionally by losing their sons, fathers and husbands. They are left powerless to survive the best they can. I always thought that the women who “keep things together” under terrible conditions are as heroic as the men fighting. Countries or generations that have not experienced war have a short memory for it. They seem unable to comprehend the extent of the long lasting, life changing traumatic effect war has on people.

I would like to mention again my mother, Jacqueline. Since as early as I can remember I always wanted to do things with my father. Just the two of us. But my father was always saying “it would be nice, but I cannot leave your mother behind.” So we always did things together as a family, never just my Dad and I. I only understood the reason behind it when I read my mother’s memoirs. As a child she had been traumatized for life by being “left behind”, on her own, amongst strangers in unfamiliar places while her mother was fighting for survival. Her mother always came back, but she was nonetheless traumatized by the fear and anxiety she felt during those moments.

It is absolutely shattering to see what is happening right now in Ukraine. It is eerie for us because it is exactly what we show in the book. Refugees, displacement, fear, lives destroyed, families separated. Mothers and children having to say goodbye to husbands and fathers who have to stay to fight, not knowing if they will ever see each other again. All things Jacqueline had to go through. And fortunately for us, all things that she and her parents survived.

The nightmare and violence inflicted on the civilians now in Ukraine will create trauma that will affect their lives forever, while the war itself will eventually be forgotten by the rest of the world. I hope our books will help children and other readers to think about those things and may help them become more careful in their choice of leaders when they grow up.

Thanks Jules and Pierre-Jacques and good luck with your book.

You can read Stella Lees review of Jacqueline here.