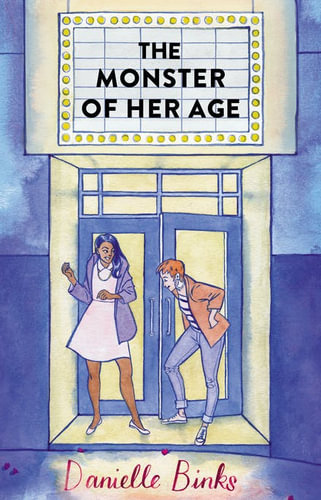

Danielle Binks, The Monster of Her Age, Hachette Australia, July 2021, 272 pp., RRP $19.99 (pbk), ISBN 9780734419736

Seventeen-year-old Ellie Marsden has travelled home to Hobart after years of running from her past because her grandmother, famous actress Lottie Lovinger, is dying. The family are gathering to say their final farewells. Lottie lived a big and complicated life, so there are multiple ex-husbands and step-siblings, as well as unresolved dramas and complex family history. But the most traumatic, unspoken issue relates to the falling out between Ellie and Lottie that spilled over into various family relationships. What actually happened is revealed slowly over the course of the story, but the impacts on Ellie’s ability to form trusting relationships are apparent from the beginning. Ellie appeared in a film with her grandmother when she was 11 years old, and the techniques used by the film makers to get her performance traumatised her. She blamed Lottie for not protecting her, and has carried the weight of this, and the impact of it on her entire family, for six years.

When Ellie becomes involved with a Feminist film club run out of Hobart’s independent State Cinema, she is forced to face her past and understand the legacy of both her grandmother’s film career and her own. This is a difficult emotional journey, complicated by Lottie’s impending death and by Ellie’s growing feelings for Riya, a young Indian woman who leads the film club.

The Monster of her Age has excellent depictions of diverse characters, showing differences of race, sexuality, disability, and religion effortlessly – as in real life, these are just aspects of who the characters are. The book is also very realistic in its depiction of end-of-life illness and death, and the impact that has on those waiting. It is a book with heart, exploring what love and forgiveness actually mean, and how trauma can impact on these. It also has an intelligent focus, exploring a range of ideas throughout, often voiced by Riya, including a feminist critique of fairy tales, a commentary on the importance of the arts and whether art can be separated from the artist, and a deep exploration of horror movies, including their music, impact, and purpose. Occasionally these discussions between Ellie and Riya verge on didactic, but overall it is good to see a book engaging with more complex ideas.

The only drawback for me, as someone who was born and raised in Hobart, and attended Ogilvie High, are the errors related to setting the story in Hobart. Every time I came across one of these it took me out of the story. But most readers will not be aware of these issues.

A heartfelt, well-constructed story about the secrets families carry and the damage they can do, set against the backdrop of the Australian film industry, with the sort of diversity that needs to become standard in novels to reflect the real world.

Reviewed by Rachel Le Rossignol